Nine-month-old Hope, at home with her parents and brother, is at this point about two months behind the usual milestones associated with infant development.

“There’s a huge spectrum of things with this syndrome,” says Vicki, seven months after Hope’s birth. “Some have certain delays or difficulties, and they range from being quite minor to being really significant. We don’t really know where she falls in yet. We are going to find out more as she grows up.”

Wolf-Hirschhorn is caused by the absence of part of the short arm in chromosome number 4. It generally causes delayed growth and development and is associated with distinctive physical features.

Since the diagnosis, Hope’s parents have been helping her develop through several exercises that target Hope’s upper-body, head support and leg extension.

“We are so fortunate to have a diagnosis so early in Hope’s life,” says dad Matthew Annis. “We have put a lot of effort into physical therapy, occupational therapy and really utilize the resources to help Hope.”

The diagnosis came as a result of work in a part of Royal Columbian that people don’t usually see. The molecular cytogenetics laboratory involves the study of chromosomes, and the hospital conducts testing for the health region, other parts of the province and even as far away as Saskatchewan.

“Royal Columbian has one of the most diverse testing menus,” says Dr. Monica Hrynchak, Royal Columbian’s cytogenetics medical director. “We do blood chromosome analysis for couples who have recurrent pregnancy losses. We do mostly chromosome microarray for children who have developmental delay or congenital abnormalities. We also do bone marrow analysis here.”

“Over the years, our ability to provide clinical care and counselling in many cases has been enhanced or made possible thanks to the work of our cytogenetic lab,” says neonatologist Dr. Zenon Cieslak.

The work is labour-intensive and in Hope’s case starts with a blood sample. Chromosomes are pulled from white blood cells by technologists using a number of techniques that offer physicians like Dr. Hrynchak an opportunity to search for abnormalities and determine whether they are significant or not.

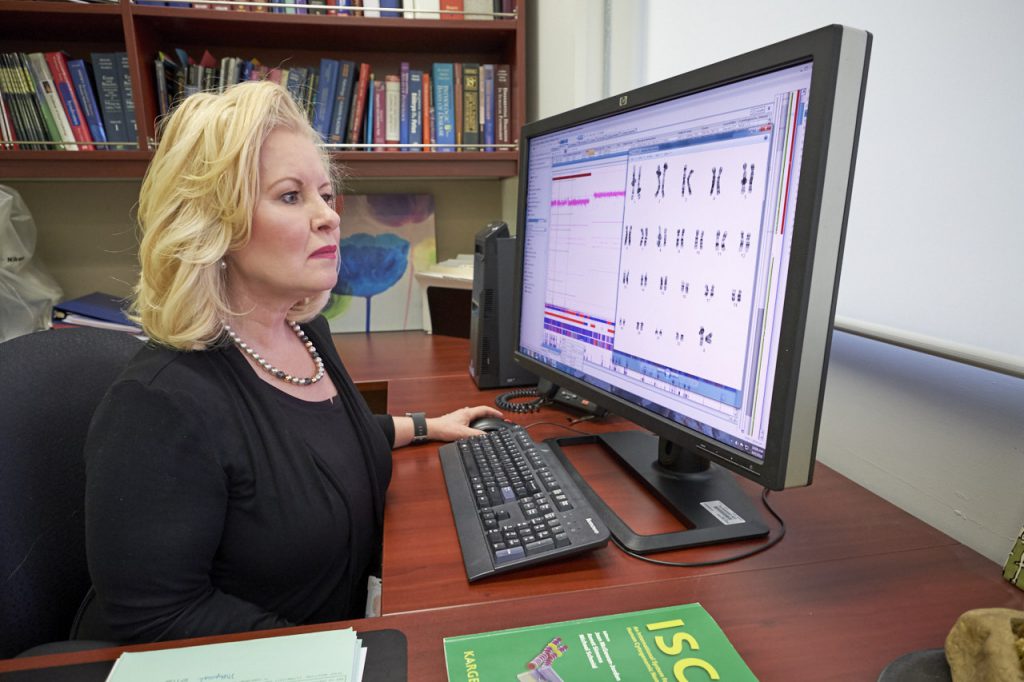

“Cytogenetics is very hands-on,” explains Dr. Hrynchak. “There’s not much automation. It’s all done manually. The biggest thing the computer does is allow us to digitally manipulate the chromosomes.”

As Royal Columbian Hospital’s cytogenetics medical director, Dr. Monica Hrynchak studies chromosomes for abnormalities that can lead to a diagnosis.

Cytogenetics has continued to evolve in the three decades since the service was first introduced at Royal Columbian. And next-generation sequencing is poised to increase the role of cytogenetics in patient care.

“It’s the next iteration of what’s going to happen in anatomical pathology,” says Dr. Hrynchak. “There are very specific genetic changes that can be identified by next-gen sequencing in specific tumours, and depending upon the change you have, it will determine what kind of treatment you get.”

“With new advancements, new techniques and progress available in genetics, its role will only continue to get more and more important in the coming years,” adds Dr. Cieslak.

Following the overwhelming emotions of the first weeks after Hope’s birth, her parents are grateful that the work of cytogenetics has focused the family on a plan for their daughter that has already led to good results.

“I am glad we know, because we have been able to get on and help her,” says Vicki. “We have already seen big changes in her. She is doing really well. She is a really happy little girl, and we are on top of trying to get her strengthened and doing all these things that are going to help her progress more.”